|

With the white stuff falling we thought we would bet everyone's grey matter working and refresh some of those backcountry safety skills

0 Comments

By Dave Bain Photo: Andy Blair Forecasts, work diary, forecasts, work diary. It is all I can look at with the storm approaching. One day is all I’ve got and the timing is on point. My mind goes to where to ride, where’s the wind been blowing and what’s the weather going to do. I dream big, I always do. My mind always goes to the western faces first. It’s my favourite place to ride by a country mile. As I pick up a mate we discuss just that. Not only are there so many epic lines, but it’s the space out there. Feels like you are actually in the mountains. And that’s just it, in the mountains. A tricky snow pack, some warm days and cold nights and now over a metre of wind blown snow on many of the lines. A voice in my head telling me it’s not on. About every twenty minutes we mention it again “what about this line” or “we could ride it like this”. Fantasize, dream, then safety, reality. The risk is too high, the reward not high enough. There is safe terrain also loaded with fresh just waiting to be slayed. The right call, the safe call is made. The western faces will still be there next time. We lap deep pow lines in the trees and mellower terrain from sun up to sun down. We hoot, we high five and our legs burn. In failing visibility late in the afternoon, two avalanches let go near us, we hear them, we spookily feel them. Stops us dead. We’re in safe terrain, it’s all good but we look at each other. Decision vindicated. The right call, the safe call and bucket loads of pow to boot. Dave Bain Photo: Dave Bain

I tour alone regularly (yes I feel the safety conscious waving their fingers already, but I take the necessary precautions that I can). The times I tour alone are for many reasons, one of them is because I like to be quiet and get lost in the world around me. But the skin track is a social place, meeting people and sharing the obligatory questions “where you headed?” and “where you been?” It’s a great bit of comradery amongst the backcountry community. Sometimes you answer in detail, sometimes not, and sometimes you don’t know! On my last tour I got chatting in a near empty Guthega carpark and we settled into a similar rhythm, chatting on the way to Illawong. Midway up Twynam another two guys on their first overnighter join the track. As we all climbed, we got chatting about locations, access and plans for the day. I was feeling like a veteran imparting knowledge to the up and comers. Classic how the ego works. And classic the dance of knowledge exchanged on the skin track. As the climbs kick in the chat lessens and the thoughts contract back in, at the same time the land around expands. Back at the top after the first line, another crew, and suddenly there are seven of us having a yarn. Conditions, lines, plans, equipment and weather. All the core subjects. Some familiar faces too, from last year’s skin track. Funny how the open spaces can pull people together. Slowly the group disbands and skin tracks diverge, different goals, different timelines. The final lines of the day I ride alone, and on the skin home cherish the space and solitude after a day on a social skin track.

DAVE BAIN An Artilce from Snow Safety Australia Ambassador Dave Bain

21st June 2017 This piece follows on from a previous article I wrote in 2012 for Protect Our Winters (POW) (Bain 2012). It takes a quick look at what the observed trends have been in Australian snowfalls over the past few decades. Regardless of people’s stance on climate change, these observations are a hard look at the likely future of Australia’s alpine environment is and our winter enjoyment. As we all know, snow cover is strongly driven by precipitation and temperature. Observed long term changes in these factors are leading to significant changes to the Australian snow pack. Snow accumulation in mainland Australia is known to show considerable inter-annual and decadal variability (Grose et al 2015) and this needs to be kept in mind. However, multiple studies have shown that snow depths at many sites have undergone long-term declines in recent decades (Davis 2013; Bhend et al 2012; Nicholls 2005; Hennessy et al 2003). In the high Australian Alps from 1950 to 2007 there has been an increase in winter temperatures approaching 1C. From 1954 to 2013, Australia has seen an overall decrease in snow depth of about 10% (Pepler et al 2015). However, these decreases have not been consistent across the snow season. The mid-winter snow depths have only decreased a small amount, whereas spring snow depth has dropped by almost 40% (Nicholls 2005) due to late season warming. Pepler et al (2015) has reported this decline in spring snow depth as an 18% decline in late September and a 30% decline in early October. These declines have occurred despite no significant changes in the average precipitation (Davis 2013) or the frequency of extreme precipitation events (Fiddes et al 2014), with snow melt being the driving force rather than a lack of snowfall during this period. Only three out of the last 15 years have had enough snow to reach the long term (1954 to present) average peak depth at Spencers Creek, and the lowest peak also occurred during this period (Domensino 2016). These figures show what many snow enthusiasts in Australia have suspected, that the snow seasons are changing. In regards to the actual storms and snowfalls across the season, light snowfalls of up to 10cm have shown a decline in frequency of about 5 days per decade since 1988. However, thankfully, the rarer heavy snowfall events have shown no change in frequency (Fiddes et al 2014). Temperatures in the Australian Alps are increasing at a greater rate in the higher altitudes than in the lower altitudes (Hennessy et al 2008). The result of these changes in snowfalls and temperatures is that the gradual build-up of snow will become less likely, making it harder to retain the snow already on the ground (Fiddes et al 2014). Some evidence of this is that there has been a 5% decline in the length of the snow season in the 2000-2013 period as compared to the 1954-1999 period (Pepler et al 2015). The outcomes of these observations for the future have been examined under predicted climate scenarios (Hennessy et al 2008; Bhend et al 2012). Declines in snow depth, an earlier end to the snow season and deceased extent of snow covered areas are projected with high confidence for the future for mainland alpine areas. In addition, there seems as though there will be even more uncertainty in predictions and seasonal outlooks. Changes in snow fall will have wide economic implications. Our snow industry is worth an estimated $1.8b employing approximately 18,000 people (Muller 2013), and is already based around a short and at times fickle snow season. In addition, the spring snow melt is very important for the hydro-electric and irrigation industries. In the very near future, if not already, snow making will have to become the dominant means of achieving an effective ski season (Hennessy et al 2008). Our unique Snowy Mountains contain highly specialised, sensitive alpine environments. This is due in part to their old age; having only minor glacial activity; and being found as a series of small alpine ‘islands’ atop of mountains within a sub-alpine ‘sea’. Our endemic alpine species have largely evolved in isolation from other continents and often on isolated mountain tops only tens of kilometres apart. Species such as the Mountain Pygmy-possum (Burramys parvus) and Broad-toothed Rat (Mastacomys fuscus) and vegetation communities such as the short alpine herbfields, alpine bogs and peatlands have very narrow environmental tolerances. These vegetation communities are reliant on long-lasting snow for a cool moist environment and are at risk from the observed changes in snowfall. Other changes may include introduced predators (foxes & cats) moving higher in the mountains because the thinner snow allows them to find alpine prey more easily (Green and Osborne 1981). One environmental change already observed is the earlier spring migration of birds to the Alps as a result of the reduction in snow (Green 2002). All of these observations do not bode well for our alpine environment, our economic industries that rely on the snowfall or all of us who enjoy and appreciate the Australian snow season. One thing is for sure though, with a shorter season and thinner snow pack, we are all going to have to make the most of those storm events when they come, as thankfully, for now we are likely to continue to see the big events occur, at least very occasionally. Further reading Bain, D (2012). https://themountainjournal.wordpress.com/environment/climate-change/climate-change-and-the-ski-industry-an-australian-perspective/ Bhend, J., Bathols, J., and Hennessy, K (2012). Climate change impacts on snow in Victoria. Aspendale, Australia: CSIRO report for the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment 42. Davis, CJ (2013). Towards the development of long-term winter records for the Snowy Mountains. Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Journal. 63: 303-313. Domensino,B(2016) Snow season high becoming a low point. http://www.weatherzone.com.au/news/snow-season-high-becoming-a-low-point/524859 Fiddes, SL., Pezza, AB., and Barras, V (2015). A new perspective on Australian snow. Atmospheric Science Letters. 16: 246-252. Green, K (2002). Impacts of global warming on the Snowy Mountains, in: Climate change impacts on biodiversity in Australia. CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra. Green, K. and Osborne, WS (1981). The diet of foxes, Vulpes vulpes in relation to abundance of prey above the winter snowline in New South Wales. Australian Wildlife Research. 8: 349-360. Grose, M. et al. (2015). Southern Slopes Cluster Report, Climate Change in Australia Projections for Australia’s Natural Resource Management Regions: Cluster Reports, eds. Ekström, M. et al., CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology, Australia. Hennessy, KJ., Whetton, PH., Smith. IN., Bathols, JM., Hutchinson, M., and Sharples, J (2003). The impact of climate change on snow conditions in mainland Australia. Report the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victorian Greenhouse Office, Parks Victoria, New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service, New South Wales Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources, Australian Greenhouse Office and Australian Ski Areas Association. CSIRO. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228606768_The_Impact_of_Climate_Change_on_Snow_Conditions_in_Mainland_Australia Hennessy, KJ., Whetton, PH., Walsh, K., Smith, IN., Bathols, JM., Hutchinson, M., Sharples, J (2008). Climate change effects on snow conditions in mainland Australia and adaptation at ski resorts through snowmaking. Climate Research 35: 255-270. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51986536_Climate_change_effects_on_snow_conditions_in_mainland_Australia_and_adaptation_at_ski_resorts_through_snowmaking Muller, G (2013). Climate change threat to $1.8b snow industry http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/bushtelegraph/alpine-tourism/5023908 Nicholls, N (2005). Climate variability, climate change and the Australian snow season. Australian Meteorological Magazine, 54, 177-185. Pepler, AS., Trewin, B., and Ganter, C (2015). The influences of climate drivers on the Australian snow season. Australian Meteorological an My brain is reeling so fast, I can’t decide whether to panic. I can’t process it. My midriff is freezing from the force of the snow and there’s a sharp pain in my shoulder. My mind must be playing tricks on me, it’s like someone knocking on a door. My ragged breath is all I hear against very unnatural silence. Something hard like metal crunches against my jacket, I feel gloved hands scrabbling at my face and down my leg. A voice yells, “It’s okay, we’ve got you”. I feel chilly fingers jerk my jaw down and scrape snow from my mouth allowing my airway to suck gratefully at mountain oxygen. My goggles are pushed back and I look up to see my friend’s face, panting with exertion and concern. Behind her, two others use metal snow shovels to dig the rest of me out. “It was an avalanche, helicopter is on its way”, I’m told. What felt like an hour has taken just six minutes. Fourteen minutes is all rescuers have in an avalanche to give the victim a 90% chance at survival. To have a 50% of survival a victim is found and dug out within 30 minutes. To make the fourteen minute deadline, rescuers have seven minutes to locate the body and another seven minutes to dig them out to access oxygen. I was lucky to be found and dug out in six minutes, I’m told later over a cold beer in the pub. I’m grateful, but somehow not surprised. Luck played no part in being with this group of like-minded skiers, we deliberately sought out industry leading avalanche awareness training that provided on-mountain rescue scenarios and all carry rescue equipment in the mountains like second skin. A backpack filled with probe sticks, sturdy metal shovel, water, first aid and an avalanche beacon strapped to each skiers’ chest, set on ‘receive’ mode but all trained to flick the switch to ‘search’ mode if and when disaster strikes. This scenario is fictitious but it’s typical of situations that not only can happen but frequently do. In the 2015/16 winter season the USA experienced 29 fatalities in a typical winter season with an average of 27 deaths. Numbers are similar for Canada at 32 deaths. It’s no surprise avalanche fatality statistics in Japan are more difficult to source online. Recreational snow sports have grown in popularity since the 1950s, but snow resorts enjoyed mostly by Japanese people are experiencing boom international growth, international visitor demand can often outstrip services such as adequate ski patrol and lift operation in many resorts, some resorts have rules forbidding ski patrol to search or collect the victim until they are dragged back inside the resort boundary by their friends. At least one resort is famous for their lift operators to go to lunch for an hour, leaving skiers and boarders to load themselves on and off chairlifts until they return. Humans by our very nature like to push the boundaries. Civilisations have flourished across continents on the backs of intrepid individuals brave enough to search for more. International snow resorts enjoy popularity with Australian snowsport enthusiasts in the pursuit of value for money, great terrain and cultural experiences they can’t get back home. The lure of ‘off-piste’ skiing is real and accessible for Australians, professional skiers and snowboarders flaunt magazines, tv shows and ski movies making international mountains look appealing. If the desire and funds for the trip is available, there is little else standing in the way of an advanced National Geographic reports that 90% of avalanche incidents are triggered by the victim or someone in their group. The worldwide statistics for fatalities sits at 150, these are just the incidents reported, the majority of victims are skiers, snowboarders and snowmobile riders. Avalanche Safety Training Level 1 is an introductory avalanche awareness course developed by Avalanche Canada (formerly called the Canadian Avalanche Centre). It is designed to give people an entry level avalanche decision making framework for using unpatrolled snow areas for recreation. It is internationally recognised and regarded as world standard. To have each of your ski party equipped with this qualification is no guarantee of absolute safety but means everyone is trained to search for a victim’s avalanche beacon in a globally standardised way and knows the timeframes to work under. There is a tried and tested method for using the avalanche beacon and a structure for best case scenario rescue. Each person gains decision making competence, gains experience assessing a variety of terrain and performs at least one mock rescue involving one to four avalanche victims somewhere high on an isolated mountain with the only way home to ski down or emergency helicopter out. Wearing and carrying proper gear is paramount to comfort out on a mountain. It’s great to save money but when you’re out in extreme elements in side or back country it’s no time to skimp on quality. Le Bent, an innovative Australian base layer company has combined the benefits of bamboo with merino wool to produce base layer tops, pants, socks, balaclavas and gloves for snow conditions . Hiking 8 km straight up the ridge from the base of the mountain ready to ski untracked powder in the NSW Snowies, the merits of this unusual bamboo-merino combo is noted and appreciated. A former user of synthetic balaclavas, the breathability of bamboo made hiking bearable, hours later when wind whipped sideways and snow swirled, those perspiration-wicking base layers really counted. The Le Bent socks with added shin layer bore the brunt of every step my cross-country skis took. And the odour-free properties were true to form. Quality boots, snow jacket and pants help with success of being out in mountainous conditions for long periods of time. Weather can change in two seconds from sunny to inclement gale, The joke of the day during my avalanche awareness course was the coffee van is right around the corner. The reality is far from that. If things go wrong with boots, socks balaclava or skis it’s a long day ahead of discomfort with blisters, extreme cold or risk of a broken ankle. You are 90% more likely to come home if there is a

female in your group. Women are more risk averse, encourage like-minded female friends to join your group rather than dissuade them based on gender alone. If you’re thinking of pushing personal limits beyond the confines of snow resorts, first think Avalanche Awareness and make your best chance of success your smartest one you’ve made all year. Look at any beginner skinner, and you’ll likely see an act of distress akin to uphill roller-skating on black ice. Look at someone who’s been at it for a while, and they might appear as comfortable sidehilling a sheen of breakable crust as a child frolicking through a meadow.

Becoming that seasoned skinner takes practice, attention to detail and, most importantly, time. But the mechanics of moving uphill are simple and easy to break down. Once dialed, walking on skis becomes efficient and second nature, meaning more laps and longer distances. Because, at the end of the day, that’s what we all want, right? Here are a few tips and tricks on how to get there. come on a Backcountry intro day to learn these skills on either Skis or Splitboard. More info can be found here snowsafety.com.au/backcountry-intro.html

The psychological impact of surviving a snowslide can produce post-traumatic stress disorder and a loop of shame and guilt

In October 2017, an avalanche on Montana’s Imp Peak claimed the life of 23-year-old Bozeman resident Inge Perkins, a rising star in the backcountry skiing and climbing worlds.

Her partner and well-known climber Hayden Kennedy, 27, survived the accident, but couldn’t locate Perkins, whose avalanche transceiver was turned off. He took his own life the following day. Kennedy’s father wrote in a public statement: “Hayden survived the avalanche, but not the unbearable loss of his partner in life.” While avalanches are a well-known hazard among winter mountain recreationalists, they are far more common than most people suspect. Historically there has been little public talk of their psychological impact, despite the fact that those swept up in avalanches, even non-fatal ones, reportedly deal with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and a unique loop of shame and guilt. But the tragedy of Kennedy and Perkins laid bare the magnitude of trauma left in an avalanche’s wake, and since then there’s been a kind of awakening among a reeling backcountry winter community.

The US is a paradise for backcountry skiing, snowboarding and snowmobiling, mostly taking place on tens of millions of wild acres of national and state forests in mountain ranges across the west and pockets in the north-east. A staggering 4.1 million people reported accessing the backcountry in 2016/17, up from 3.2 million only a couple years earlier.

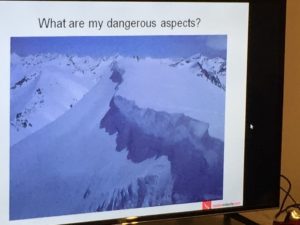

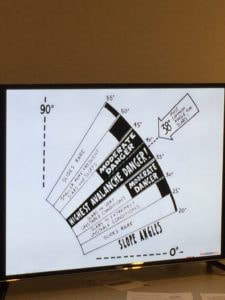

For many backcountry enthusiasts, the allure of the backcountry is the promise of deep powder. For others it is the solitude, or fulfilling a deep-rooted need for exploration and adventure that’s increasingly hard to find in an era of Google Maps. A few might not be able to articulate it at all, except to say that spending time in the backcountry makes them feel more alive. “When you’re out there and you’re tickling the dragon, you have an appreciation for the fragility of life,” explains Christian Beckwith, founder of Alpinist magazine. “And you don’t get that without having the dragon wake up sometimes.” Backcountry snowsports require mastery of an enormous amount of information, including knowledge of snow science and how weather and terrain can affect the snow pack, and practitioners should have an eye for weaknesses that can cause slabs of snow to release naturally or as a result of human triggers. Setting off an avalanche might indicate a gap in that knowledge – a mistake of sometimes fatal proportions. An average of 27 people die in US avalanches each winter. “Embarrassment is one of the main reasons people don’t talk about their avalanche accidents,” said professional skier Elyse Saugstad, who was part of the 2012 Tunnel Creek avalanche outside Stevens Pass in central Washington state that received national attention, mostly because it involved a group of more than a dozen highly knowledgeable people in the ski and snowboard industry. The avalanche swept up Saugstad, who pulled her airbag, and three other skiers – Jim Jack, Chris Rudolph and John Brenan – who were killed in the slide. "Especially among the pros, you don’t want people thinking you made a mistake, because you’re afraid of the judgment that inevitably comes when you do. But even highly professional people in the industry make mistakes.” To channel her trauma after the accident, Saugstad threw herself into education around avalanche airbags, which were a new device at the time designed to float skiers to the top of moving slide debris. She didn’t want her friends’ deaths to be in vain and hoped people could learn from her nightmarish experience. But she said others didn’t see it that way, and leveled accusations that she was using her accident to promote a product. On top of that, she felt judgment in people sifting through the mistakes the group made that day. “I understood that people would judge what happened, so I did my best to shut out the negative criticisms. I had already lost my friends and that was bad enough. Just as long as I was honest with myself about the mistakes we made and objectively go over what I personally did wrong alongside the group, that was enough.”

Along with PTSD, anxiety and depression, shame is a common response among those caught up in avalanches, said Jennifer Feibig, a therapist practicing in Bozeman, Montana, who regularly treats people who have been involved in avalanche accidents.

“There’s a culture of analyzing all the data after an accident that takes all the humanity out of the survivors, who are already thinking ‘I killed my friend’ or going through other grief, and then descending into a shame spiral on top of that,” she said. “We need to know what happened, but we also need to make that space for the survivor to feel cared for, to feel validated that they did the best they could do, and recognize the pain that they just went through.” These emotions described by Feibig are familiar to the Helena, Montana-based couple Melissa Hornbein, a lawyer, and Aaron Gams, a nurse. On Memorial Day weekend in 2011, they took a break from busy lives to take advantage of the prime time for steep spring skiing in the mountains. The last thing Hornbein recalls is stopping at a grocery store on the way up Wyoming’s Togwotee Pass. The rest she has had to reconstruct: she and Gams climbed the final pitch of the snowy chute, the skis strapped to their packs swaying with each step kicked into the steep face. There was a split second when the top layer of snow cracked, a sight straight out of every backcountry skier’s worst nightmare. Hornbein was swept over cliffs by the avalanche and woke up in the hospital with a fractured pelvis, fractured skull and a dozen broken teeth. “Were we in an avalanche?” was the first thing she asked. That day haunted them both. The sudden sensation of falling would engulf Hornbein out of nowhere for years after the accident. Even in the safest of skiing conditions, she experienced overwhelming physical responses – heart pounding, sweating, panic – and sometimes called off the mission. “I didn’t know if the fear was completely visceral or if it was rooted in actual danger,” she said. “What that avalanche took away from me was knowing how to trust myself.” In her everyday life, she becomes anxious when she doesn’t have control, which manifested particularly vividly after the birth of her daughter, now aged one and a half. “For the first six months or so, I worried so much about this little baby and having no control over what’s going on with her health and development … I was hypervigilant, worried that if I wasn’t constantly on alert, something would happen to her.” Gams remembers everything of the accident. As the slide came to rest, he realized he was only partially buried and he scanned the debris for Melissa. He spotted her immediately, only partially buried as well – but she was unconscious, with blood trickling from her ear. With all three major ligaments torn in his knee and a separated shoulder, he pulled Melissa out of the debris and wrestled them both through the snow out to the road, where he flagged down a passing car. Despite this heroic effort, he said, “I felt like I had massively screwed up – I was the one who was pushing for going higher. I was so worried I had really messed up Melissa. I was feeling guilty right away”. Saugstad believes that bringing avalanche trauma into the open – and taking judgment out of the equation – starts with professionals telling their own stories publicly. Beckwith, the founder of Alpinist, agrees. His own accident occurred in 2013, when he was skiing Prospectors Mountain in Wyoming’s Grand Teton national park with good friend and fellow Jackson Hole resident Jared Spackman. An avalanche broke above them as they were ascending the Apocalypse Couloir, and the slide carried Spackman 1,000 vertical feet down the narrow chute, claiming his life. Beckwith was unscathed. “The bomb goes off, shattering all equilibrium,” he said, speaking quietly of the aftermath. “Eventually, the ringing in your ears begins to subside, the dust begins to settle. You realize you’re in the bottom of the crater, and you do your best to crawl out of the bomb hole, stagger to your feet and begin walking in the direction you think is right.” Beckwith sees the backcountry winter community itself as uniquely positioned to support its members. “We’ve chosen a lifestyle in which loss is inherent, so a support structure is organically part of the community. It’s a tribe, and its members understand the deal, and one another.” Cassidy Randall The Guardian |

Archives

March 2022

AuthorSnow Safety Australia is a NSW based information website. Categories |

Training Courses |

Company |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed